Examining UBS's Profit-Led Inflation Theory

UBS recently proposed an informal theory of profit-led inflation. The theory suffers from three issues—so more work is required to understand greedflation.

A memo from Paul Donovan, Chief Economist at UBS, has been causing a stir on Twitter recently. In it, Donovan argues that inflation was driven by corporate greed in the aftermath of the pandemic. That is, we experienced greedflation.

Donovan’s memo is interesting because it lays out precisely how he thinks greedflation operates. This post examines Donovan’s informal theory and compares it to the formal pricing theory developed by Erik Eyster, Kristof Madarasz, and I in a 2021 paper titled “Pricing under Fairness Concerns”. I bring up our theory here because it shares all the elements of Donovan’s theory—unlike more standard pricing theories. It therefore provides a formal foundation to the ideas proposed by Donovan, and it can be used to check the logic of Donovan’s argument.1

UBS’s theory of profit-led inflation

So what is Donovan’s theory of profit-led inflation? He articulates it as follows:

Developed economies have had three waves of inflation since the pandemic: transitory inflation for durable goods; commodity inflation; and finally profit margin-led inflation.

Profit margin-led inflation is not caused by a supply-demand imbalance. Profit margin-led inflation is when some companies spin a story that convinces customers that price increases are "fair, " when in fact they disguise profit margin expansion.

Technically, companies are able to use stories to reduce their customer's price elasticity of demand.

Raising rates to reduce demand will eventually squeeze profit margin-led inflation, but it is a crude and unnecessarily destructive policy approach.

Convincing consumers not to passively accept the price increases is a potentially faster and less destructive way of reversing profit margin-led inflation. Social media might have a role to play in this process.

This theory involves three interesting elements: concerns about the fairness of prices, stories that influence perceptions of fairness, and variable price elasticity of demand.

While a variable elasticity of demand is present in several pricing models, fairness concerns and stories are not. There are a few papers that introduce fairness concerns into pricing, most notably by Julio Rotemberg. There is also some work on stories in macroeconomics, principally by Robert Shiller. But overall, these are uncommon assumptions in pricing models.

Our theory of pricing under fairness concerns, on the other hand, involves the exact same three elements as Donovan’s theory.

Our theory of pricing under fairness concerns

Our theory first assumption is that customers care about the fairness of prices. Customers dislike unfair prices, which are prices marked up steeply over cost. They like fair prices, which are those with a low markup over cost. Formally, in the utility function, we assume that each unit of consumption is weighted by a fairness function that is decreasing in the markup perceived by customers. A lot of evidence suggests that people’s perceptions of fairness and unfairness are influenced by markups, as discussed in a previous post.

The second assumption is that customers do not observe firms’ costs, so they must infer them from prices. A key element of the theory is that customers infer less than rationally. When a price rises due to a cost increase, customers partially misattribute the higher price to a higher markup—which they find unfair. Conversely, when a price falls thanks to a cost decrease, customers partially misattribute the lower price to a lower markup. This is just a form of money illusion.

These perceived marginal costs are beliefs that customers hold about firm’s costs. They could be influenced by the stories mentioned in Donovan’s theory. If a firm is able to convince customers that their costs have increased, then perceived marginal costs will increase. Indeed, firms often try to explain to their customers that their costs have increased and that they had no choice but increase their prices in response.

I have collected a lot of anecdotal evidence of such stories over the years. Here is a taqueria announcing an increase in the cost of avocados:

Here is an increase in the cost of garlic announced at an Indian restaurant:

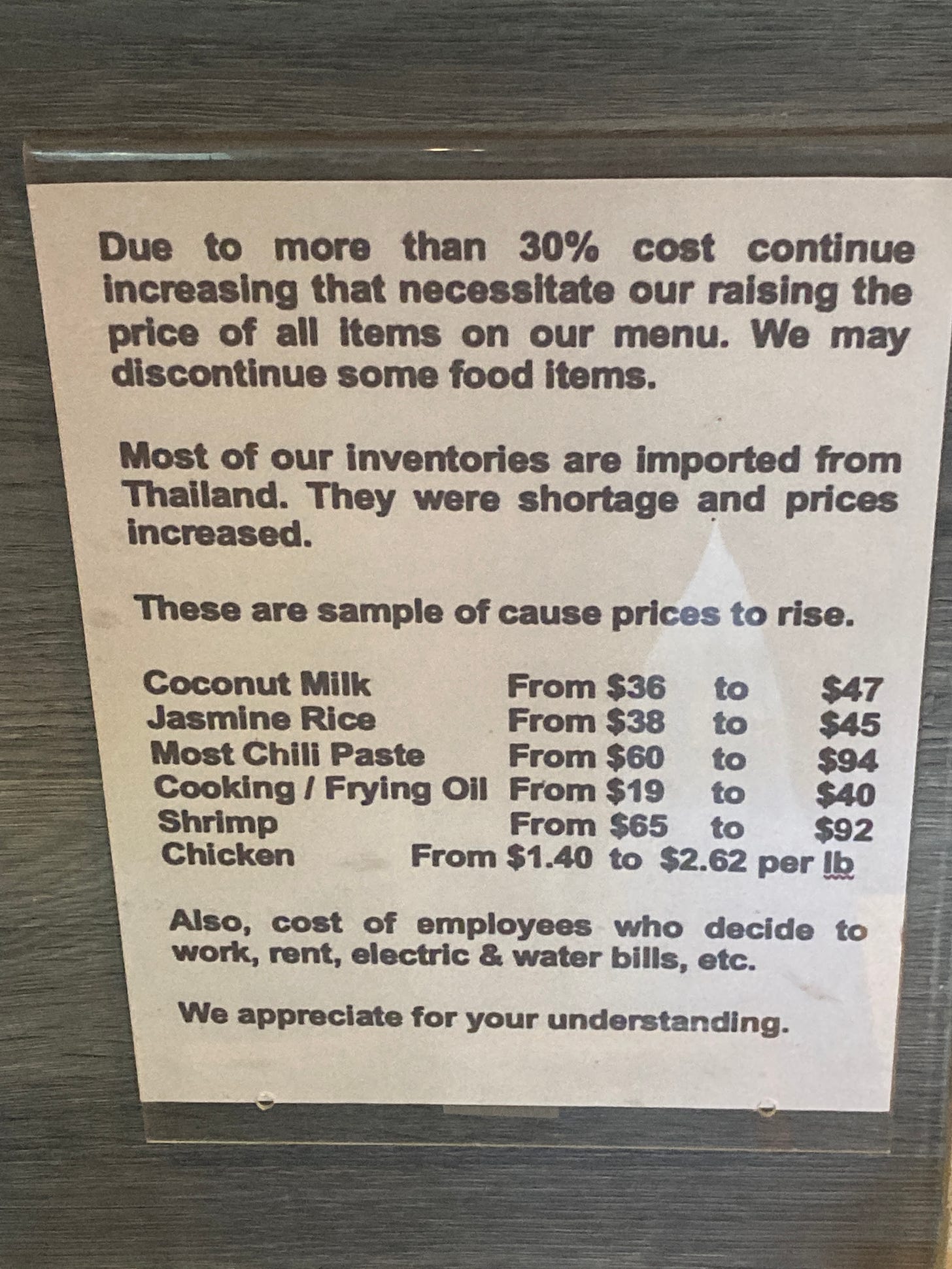

Here is a generalized increase in costs at a Thai restaurant:

Finally, here is an increase in the cost of foodstuff at a sausage shop:

It does appear that when costs go up significantly, firms try to explain the increase to customers as they raise prices. The goal of course is to raise the marginal cost that customers perceive so as to reduce the perceived markup—and in turn increase the perceived fairness of the transaction.

The particularly interesting connection between Donovan’s theory and ours is how perceived fairness affects pricing. In general, theories of fair pricing assume that customers refuse to shop at unfair stores (see for instance this paper by Julio Rotemberg). Our theory is a little different. Because fairness affects the marginal utility from consumption, it ends up influencing the price elasticity of demand faced by firms. When customers deem a transaction fair, the price elasticity of demand is lower; when they deem it unfair, the price elasticity of demand is higher. In other words, customers are more price sensitive when they feel unfairly treated.

As it happens, Donovan makes the same assumption. Unlike in standard models, firms’ demand curves have the property that when perceived markups are higher, transactions are seen as les fair, and demand curves are more elastic. This means that the perceived fairness of a transaction affects the markups that firms charge. In such models of monopolistic pricing, the profit-maximizing markup is a decreasing function of the price elasticity of demand. So when the price elasticity of demand is lower, firms will charge higher markups and make larger profits. By influencing the price elasticity of demand, perceived fairness also influences the markups that firms charge and the profits they make.

Overall, our theory of pricing under fairness concerns involves the exact same three elements as Donovan’s theory: concerns about the fairness of markups, beliefs about marginal costs that are not entirely rational and could be influenced by stories, and a connection between perceived fairness and the price elasticity of demand. Our theory therefore provides a formal foundation to the ideas proposed by Donovan. It can also be used to check the logic and implications of Donovan’s argument.

First issue with UBS’s theory: nobody thought pandemic price increases were fair

Donovan argues that firm raised markups (profit margins) after the pandemic because they managed to convince customers that the new prices were fair. Indeed, in our theory too, firms would choose to raise their markups if they had convinced customers that marginal costs had risen (although they had not).

The underlying reason is that when customers feel treated more fairly, the price elasticity of demand is lower, so the profit-maximizing markup is higher. A firm that does not face higher costs wants to raise prices only if the elasticity of demand falls. This occurs only if customers think transactions are fairer.

The implication of the argument is that after the pandemic, people thought that firms were more fair than before. This is what, supposedly, allowed firms to raise profit margins and fueled inflation.

But the opposite seems true. People have been upset about the greed of corporations and worried about price gouging since the very beginning of the pandemic. In fact, as early as April 2020, Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris introduced a bill in Congress to crack down on price gouging during the coronavirus pandemic.

Several similar bills were introduced in 2021 and 2022, indicating that concerns over unfair prices and price gouging continuously prevailed during the pandemic. And a huge amount of press articles, blog posts, and online discussions were devoted to these topics during the span of the pandemic.

So the idea that firms were able to raise markups because they convinced consumers that such price increases were fair seems unrealistic. Accordingly, using social media to tell people that prices are unfair does not seem very promising. People are all too aware of inflation, and are already upset by it.

Second issue with UBS’s theory: why increase markups now?

Why did firms choose to increase prices at all during the pandemic? If they could convince customers that higher prices were fair in 2022, why didn’t they convince them in 2019 instead? or in 2015? Why wait all this time to pocket higher profits?

Although not mentioned explicitly by Donovan, it seems likely that firms started to increase prices in response the supply-chain disruptions and commodity-cost increases triggered by the pandemic. Then, presumably, firms increased prices in an exaggerated manner to raise markups and pocket higher profits.

But the issue with this theory is the same again: why raise markups now? Why didn't firms raise markups before the price increase?

In an early version of our paper we studied a situation in which costs increase—just like they did during the pandemic—and firms have the option to disclose costs to customers. We found that it was optimal for firms to disclose cost increases, and that cost increases were fully passed through—but not more. That is, firms described the increase in cost to customers, they raised prices accordingly (say, a 10% price increase followed a 10% cost increase), but they did not raise markups.

So markups remain the same after a disclosed cost increase. They do not increase, unlike in Donovan’s theory. The reason is that markups were chosen optimally before the cost change, so there is no reason to increase them after the change. Convincing customers that costs have increased does not imply that markups increase. Firms disclose costs only to protect their previous markups, not to increase them.

In this extension of the model, firms disclose cost changes truthfully, and customers believe them. Maybe firms lied to customers and exaggerated the cost increases that they faced. The public outrage at price increases during the pandemic suggests however that firms did not manage to convince customers that markups were lower than before. Facing such outraged customers, firms would never find it optimal to charge higher markups than before.

Third issue with UBS’s theory: the role of monetary policy

We saw above that the social-media approach to fighting inflation is unlikely to be successful. Another approach mentioned in the UBS document is monetary policy, which could squeeze profit margins and reduce inflation.

Actually, in the type of models discussed here, monetary policy does not works that way. When the Fed raises rates, demand falls and inflation starts falling. Consumers face less inflation than they are used to. They attribute such unusually low prices partially to lower markups, which they find fair. Firms take advantage of this misperception to raise markups! These higher markups reduce economic activity, explaining why higher interest rates are contractionary.

The relevant aspect of the story is that markups are actually higher when the Fed tightens monetary policy. (And indeed, price markups seem countercyclical in US data.) So monetary policy would not be a useful tool to reduce profit margins.

Conclusion

All in all, UBS’s theory of profit-led inflation features interesting elements, but it is inconsistent with the public outrage at price increases that started in the first months of the pandemic. In this type of model, it is not possible to have both higher markups and public outrage at unfair prices.

So either markups did not rise after the pandemic, and inflation was not profit-led after all. Or markups did rise, but then another theory is required to explain why firms found it optimal to raise markups while upsetting their customers.

Thanks to Wojtek Kopczuk, David Baqaee, Maor Milgrom, Dudu Lagziel, Itamar Caspi, and Eli Cook for conversations that inspired this post.