Why Do People Dislike Inflation? Using Shiller's Findings to Revamp Inflation Models

Solving the tradeoff between inflation and financial stability is difficult because standard macro models do not capture well the costs of inflation.

Over the past two years Jay Powell’s job was easy. From the middle of 2021 to early 2023, inflation was over its 2% target, and the labor market was inefficiently tight. So the Fed did not face any tradeoff. The only thing Jay had to do was tightening monetary policy to reduce inflation and cool down the labor market.

Things are more complicated now. The recent failure of Silicon Valley Bank and demise of Credit Suisse have ushered in a period of financial instability. Before raising rates further, the Fed must weight how much it wants to reduce inflation and to cool the labor market—which require higher rates—versus how much it wants to support struggling banks—which might require lower rates.

This calculation is particularly difficult because the macro models that the Fed uses do not capture well the costs of inflation. This post discusses the reasons why inflation is so costly, and shows how such costs could be incorporated into modern macro models.

The cost of inflation: macro models versus reality

Most macro models used by central banks these days are built from the New Keynesian model. In this model, the cost of inflation comes from the price dispersion inflation generates. Firms can only change their prices at irregular intervals, and some firms are stuck with old prices for a very long time. When there is inflation, all prices drift upward, but because of staggered pricing, firms end up charging very different prices for comparable products. The resulting price dispersion is the reason why inflation is costly in the model.

Of course, price dispersion does not seem to be the reason why inflation is so problematic. David Romer, in his textbook, summarizes the situation as follows:

Inflation's costs are not well understood. There is a wide gap between the popular view of inflation and the costs of inflation that economists can identify. Inflation is intensely disliked. In periods when inflation is moderately high in the United States, for example, it is often cited in opinion polls as the most important problem facing the country. It appears to have an important effect on the outcome of Presidential elections, and it is blamed for a wide array of problems. Yet economists have difficulty in identifying substantial costs of inflation.

The discrepancy between people's view of inflation and economists' view of inflation also appeared in a New York Times column by Peter Coy last year. Coy noted that people viscerally hated inflation. But the economists he talked to did not associate large costs to inflation. Coy concluded that people should worry less about inflation. Another possible conclusion, which this post explores, is that macroeconomic models should capture people's sentiments better and ascribe larger costs to inflation.

So why do people dislike inflation?

Robert Shiller has a wonderful paper titled “Why Do People Dislike Inflation?” in which he explores the reasons why people are so averse to inflation. The paper is based on surveys of regular people in the United States, Germany, and Brazil in the 1990s. Shiller’s goal is

to try to understand, using public survey methods, why people are so concerned and dismayed by inflation, the increase in the price level, and decline in value of money. Studying public attitudes toward inflation may help government policymakers better understand the reasons that they should (or should not) be very concerned with controlling inflation.

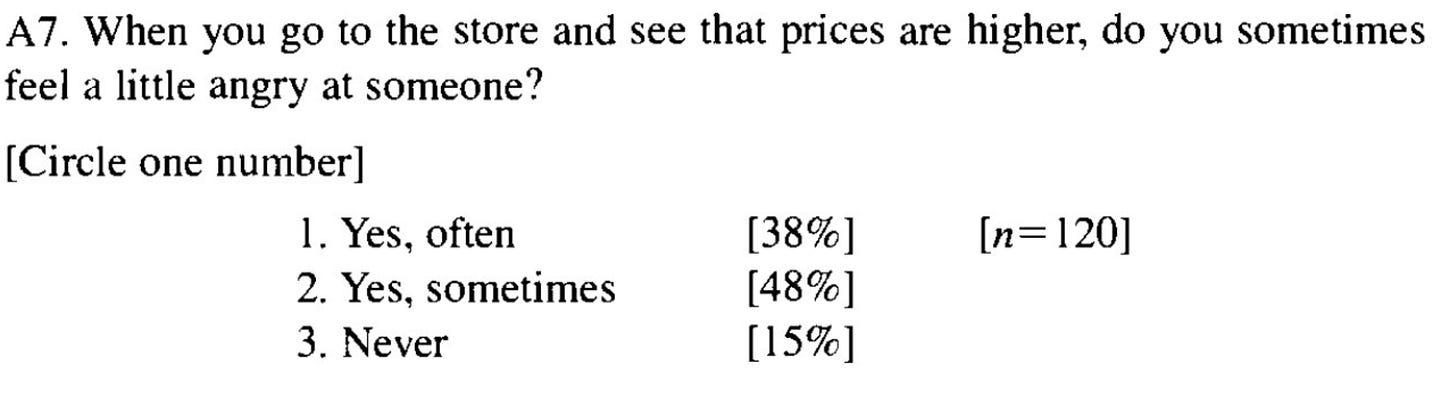

The first finding of Shiller's survey is that almost everybody thinks that controlling inflation should be a high priority for policymakers. Below is the breakdown of the survey responses:

Shiller then tried to understand why people cared so much about inflation. He started by asking respondents why, according to them, inflation occurs. He found that many people ascribed inflation to greed.

Asking people to list the causes of inflation reveal that people haven't any clear sense what is causing inflation; there are very many different factors that they think might be responsible. The most common cause cited was greed. The word "greed" or "greedy" was volunteered by 17 (16%) of the respondents.

Another 9 (8%) of the respondents blamed “big business and corporate profits” for inflation.

Given that people blame greed and businesses for inflation, Shiller investigated how people feel when they go to the store during inflationary periods. A key finding is that most people become angry when they see higher prices.

Then, Shiller asked respondents who they were angry at:

There was little agreement on who they are angry at. The government was mentioned by 18 respondents, manufacturers by 15, store owners by 6, business in general by 6, wholesalers by 4, executives by 3, the U.S. Congress by 3, and greedy people by 3.

Overall, a good number of people (31 respondents) are angry at the business community.

Accusations of price gouging and corporate greed are not surprising

After the pandemic, macroeconomists were puzzled by people's reaction to inflation. They could not understand why people were so riled up about corporate greed. But given the results from Shiller's survey, people’s reaction was completely predictable. People always feel angry when inflation creates higher prices, and they always ascribe such price increases to greed.

It is also unsurprising that politicians such as Elizabeth Warren were pushing to fight back price gouging. Indeed, their constituents thought that they were being gouged.

A macro model in which people dislike inflation

To improve our understanding of inflation and its welfare cost, we therefore need a macro model that incorporates people's actual reaction to price changes, as described in Shiller’s survey.

In a paper published in 2021, Erik Eyster, Kristof Madarasz, and I build such a macro model. The model attempts to capture people's actual reaction to price changes and inflation, to describe firms’ pricing in such a world, and to articulate the impact of monetary policy.

The paper is only a first step, but it demystifies people's visceral aversion to inflation. It also explains why the Fed and other central banks are intent on lowering inflation further—as evidenced by the recent rate increases in Europe and the United States.1

First psychological assumption: people find high markups to be unfair

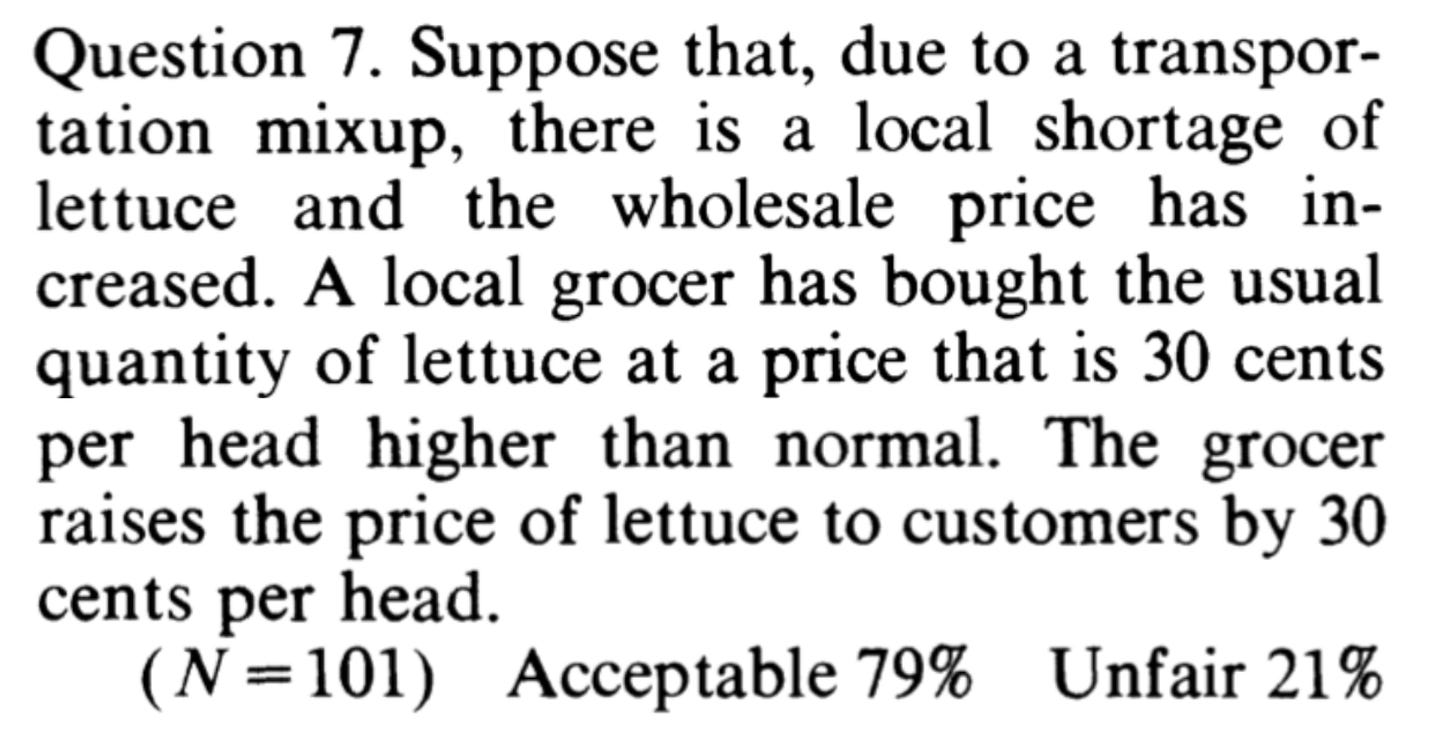

We build the model around results from psychology & economics. First, we use the results about price fairness obtained by Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler.

The first result is that a higher price due to a higher markup is unfair:

The second result is that a higher price due to a higher cost but with the same markup is fair:

These results mean that people find higher markups to be unfair, but they tolerate higher prices if their markups are unchanged.

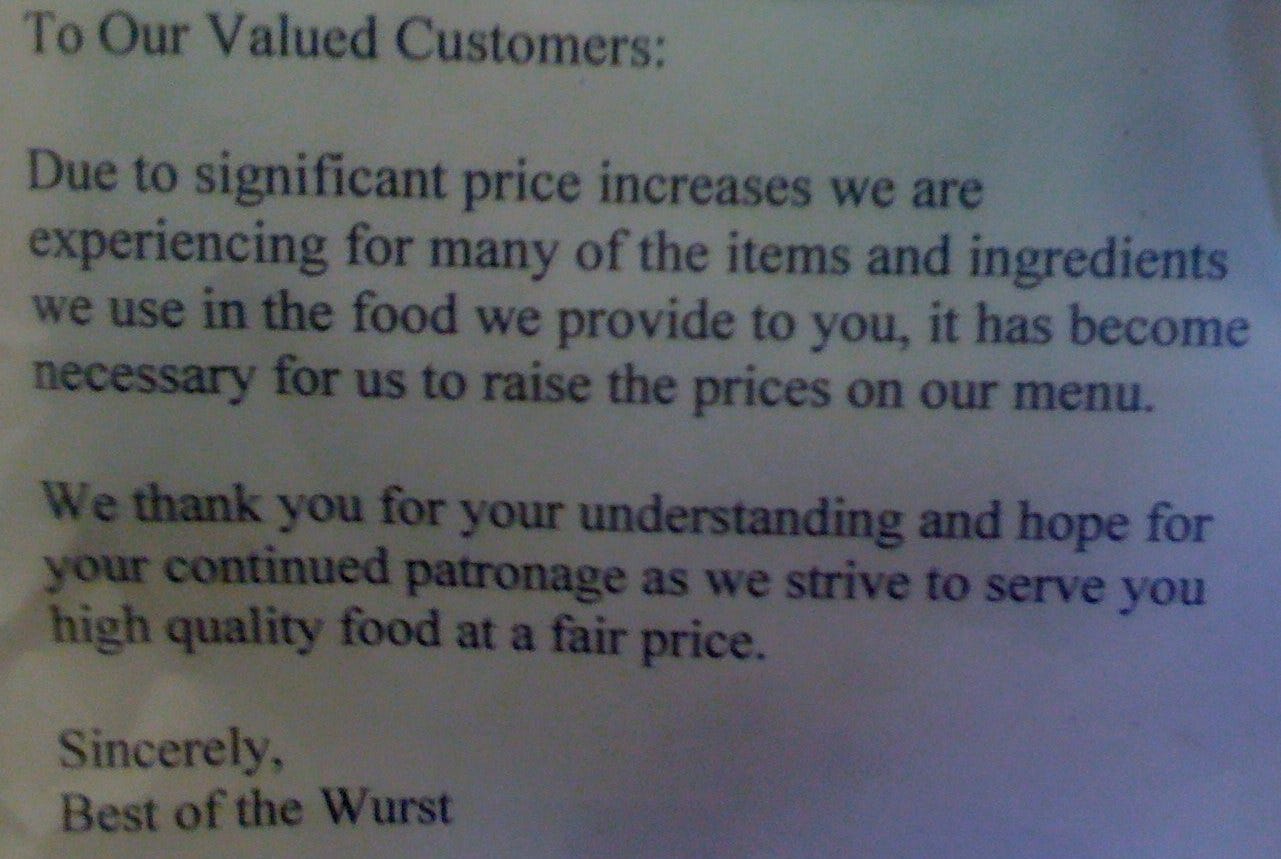

These results explain why shops that face higher costs often post signs justifying the resulting higher prices:

Firms understand that customers find higher markups to be unfair

Firms understand these norms of fairness perfectly well. In many surveys, firms describe the norm for fair pricing as a constant markup over cost. In a survey of 200 US firms, 64% of firms say that customers do not tolerate price increases after demand increases, whereas 71% of firms say that customers do tolerate price increase after cost increases. Even going back to 1939, businessmen in the United Kingdom explained the “right price”, the one which “ought to be charged," was a constant markup (generally 10%) over cost.

Even God frowns upon high markups

In fact, in Talmudic law, the maximum markup allowable in trade is 20% (corresponding to a profit margin of 1-1/1.2 = 16.7%):

Talmudic laws concerning price markups were quite explicit. Any profit from the sale of a commodity deemed necessary for life was not to exceed one sixth (16.7%). The following case demonstrates how serious was the application of this one-sixth rule. Rabbi Judah was a wine merchant; he would sell six jugs of wine for one zuz. Since one barrel (48 jugs) cost him six zuz, his profit was 12 jugs per barrel. However, after allowing for absorption of wine into the barrel, the Talmud determined that his profit margin was only 4 jugs to the barrel—a one-twelfth profit margin. Did Rabbi Judah, then, not allow himself a profit of one sixth? Well, his profits were increased by the sale of the lees and the barrel itself. In that case, however, his profit was more than one sixth. The Talmud concluded that, after accounting for Rabbi Judah's own labor and for the cost of the crier who announced the availability of the wares, the wine merchant's profit margin was one sixth. Apparently, the Talmud believed that the one-sixth markup allowed should be based upon the total cost incurred.

Second psychological assumption: people suffer from money illusion so they misperceive markups

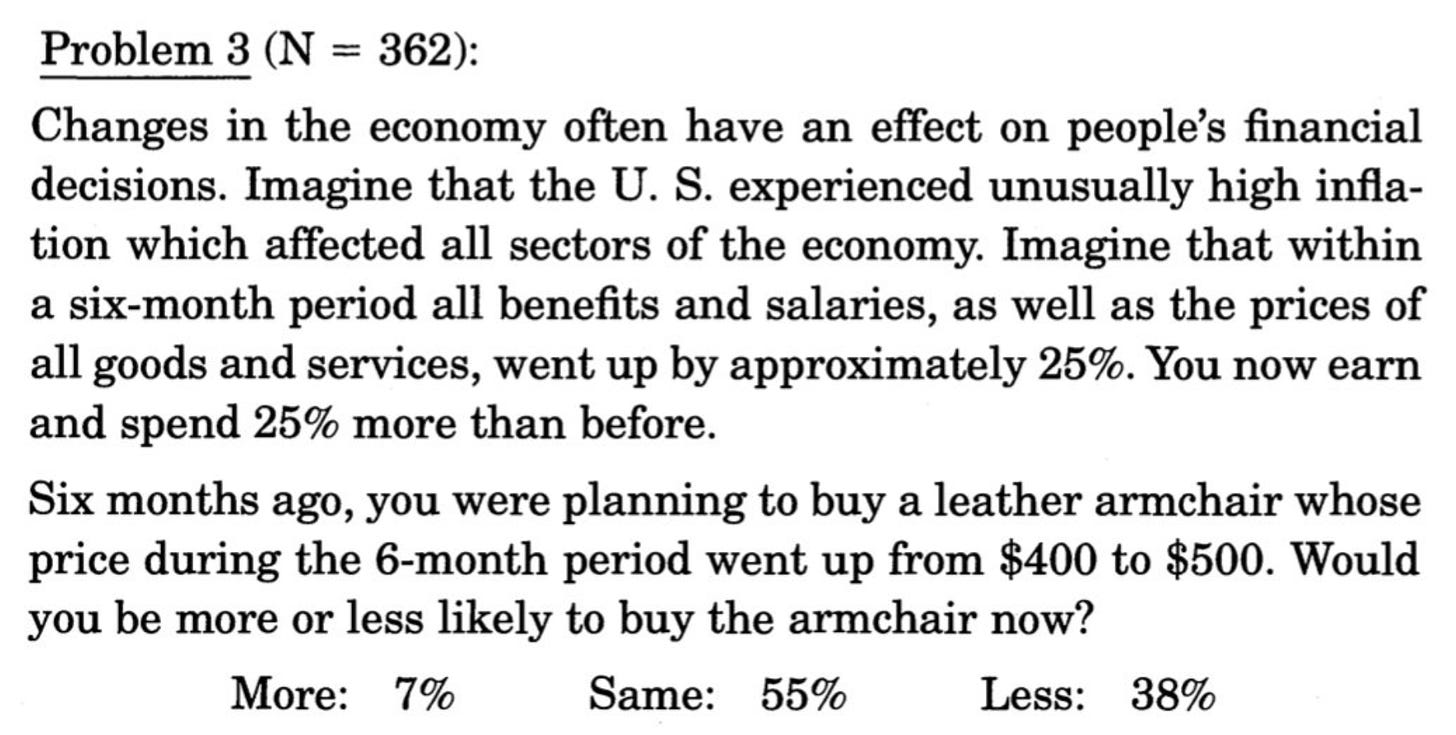

People cannot observe firms' costs, so they must infer firms’ markups from the prices they see and their understanding of the economy. People are prone to developing mistaken beliefs, however. Indeed, Eldar Shafir, Peter Diamond, and Amos Tversky discovered that people suffer from money illusion. Thus people are likely to misinfer the nominal costs faced by firms. If costs go up, people are likely to underestimate the increase. If costs go down, they are likely to underestimate the decrease. This error appears for instance in the responses to this thought experiment:

In the thought experiment nothing has really changed over the six-month period, so everybody should be as likely to buy the chair now as before. But 38% of respondents think that the deal is worse now, in all likelihood because they do not realize that the chair’s cost has increased in tandem with its price.

Overview of the model

Given the psychological evidence, we build our macro model around two assumptions:

People dislike prices marked up steeply over cost, which they find unfair.

People cannot observe firms' costs, and by money illusion they underestimate changes in nominal costs.

In the model, firms are aware of people’s preferences and beliefs, and they set prices accordingly. These two assumptions will affect how firms set prices, and determine the effectiveness of monetary policy and the cost of inflation.2

Beside these two assumptions, the rest of the model adopts a standard New Keynesian form.

First result: price rigidity

The model produces incomplete passthrough of marginal costs into prices, especially in less competitive markets. This means that if a firm’s cost increases by $1, the firm will choose to increase its price by less than $1.

The reason? When a price rises due to a cost increase, customers partially misattribute the higher price to a higher markup—which they find unfair. Firms anticipate this response and trim their price increases, which drives the passthrough of costs into prices below 1.

The result that prices do not fully respond to cost shocks is consistent with evidence on real firm behavior. For instance, in Sweden, the passthrough of cost changes into prices is only 0.3. Following trade liberalization in India, costs fell significantly due to the import tariff reduction, yet prices failed to fall in step: the passthroughs are estimated to be around 0.3–0.4. In Mexican manufacturing firms, passthrough of cost changes into prices is modest: between 0.2 and 0.4. Last, US manufacturing firms only pass through 50%–70% of cost changes caused by energy-price variations into prices.

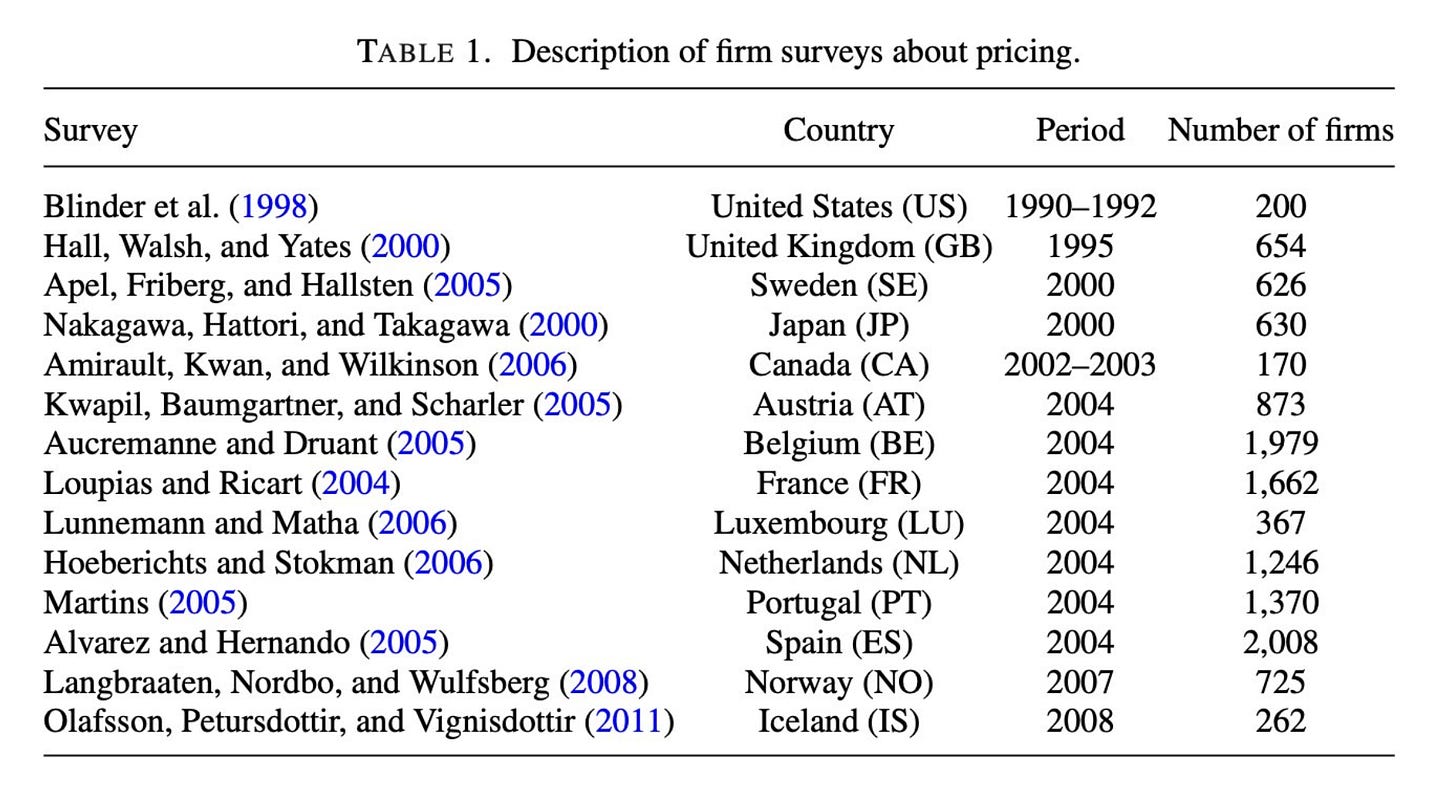

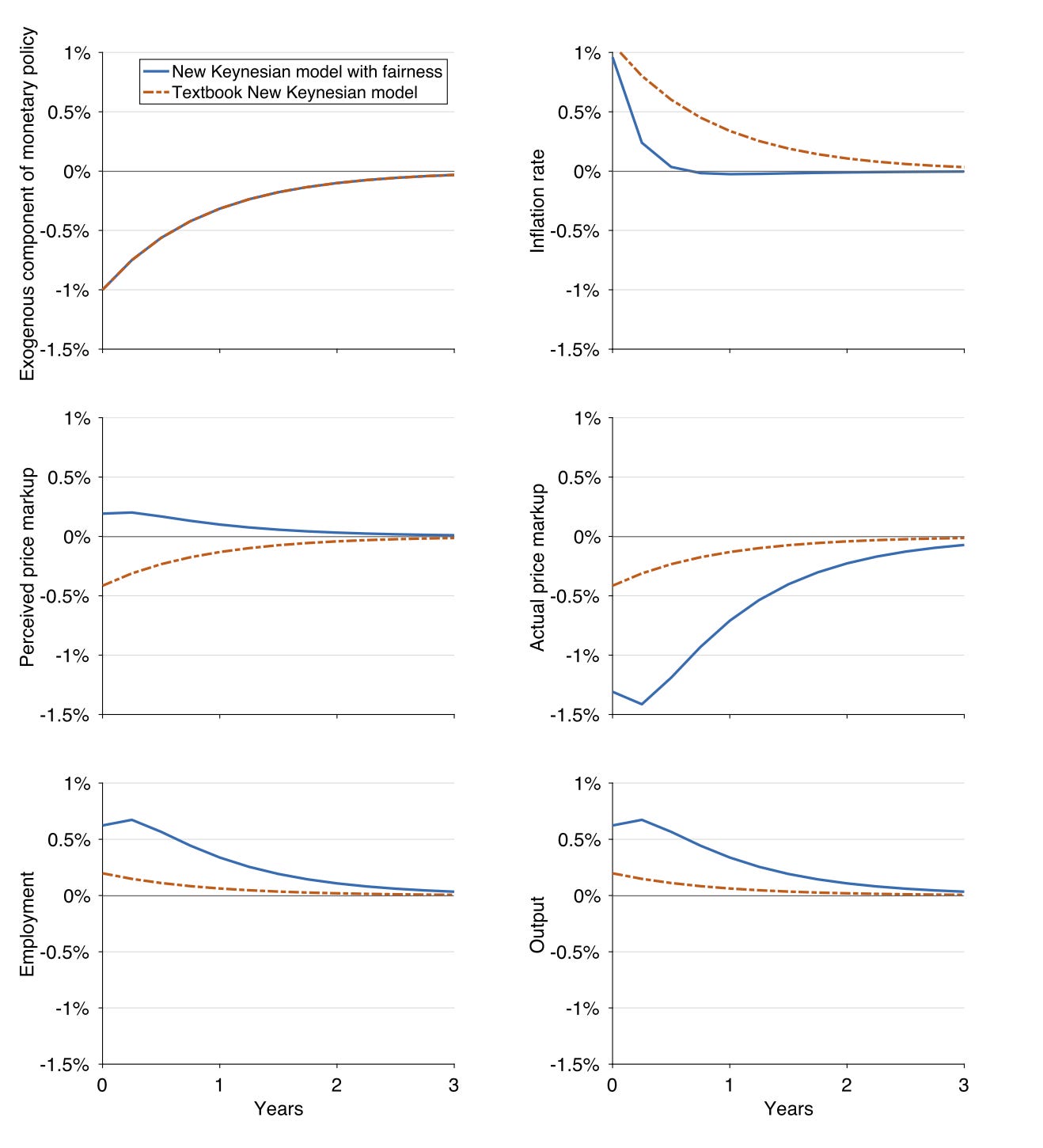

Because the cost passthrough is incomplete, the model produces price rigidity. Moreover, the mechanism for price rigidity is consistent with survey evidence that firms modulate price changes to avoid angering customers. Firm surveys about pricing have been conducted in numerous countries:

Across these surveys, firms report that the main reason why they do not change prices more often is implicit contract with customers: "firms tacitly agree to stabilize prices, perhaps out of fairness to customers".

The popular macro theory of menu costs is among the least realistic theories of price rigidity, according to firms.

Second result: monetary nonneutrality in the short run

Because of price rigidity, monetary policy is nonneutral in the short run. This means that a temporary change in monetary policy impacts both output and inflation.

When monetary policy loosens and inflation rises, customers misperceive markups as higher and feel unfairly treated. Firms mitigate the perceived unfairness by reducing their markups. Overall, employment and output rise.

Conversely when monetary policy tightens and inflation falls, customers misperceive markups as lower and feel fairly treated. Firms take advantage of the perceived fairness by raising their markups. Overall, employment and output fall.

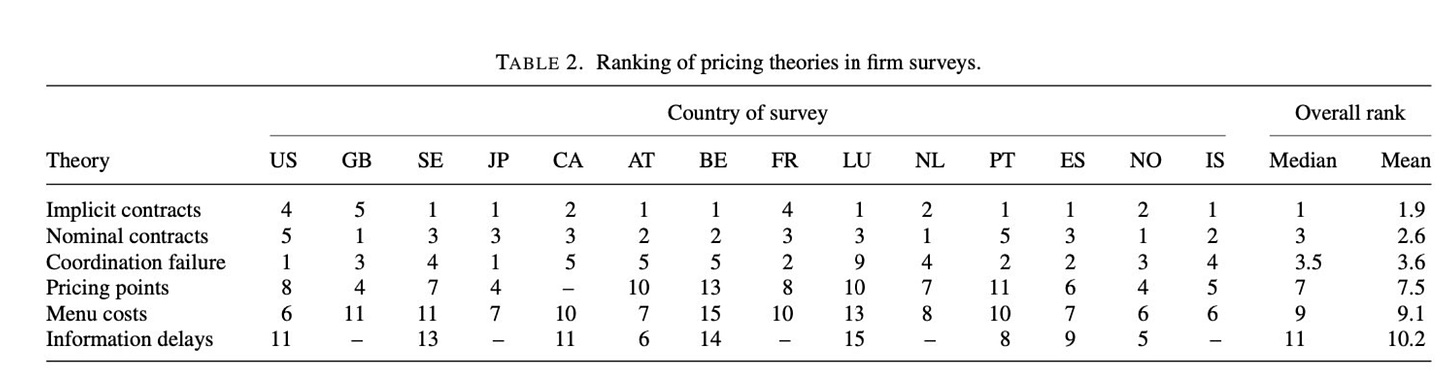

This figure below describes the impulse response of our New Keynesian model with fairness to a temporary loosening of monetary policy (solid lines). For comparison, the figure also displays the impulse response of the textbook New Keynesian model (dashed lines).

Although our macroeconomic model relies on unorthodox psychological assumptions, the quantitative properties of the impulse responses are consistent with US evidence:

Monetary policy is nonneutral in the model because monetary shocks influence output and employment. The nonneutrality of monetary policy is well documented.

The effect of monetary policy is mediated by a hybrid Phillips curve, which is realistic as both past inflation and expected future inflation enter significantly in estimated New Keynesian Phillips curve.

The shape of the response of output to monetary policy is the same as in the data, as output is estimated to respond in a hump-shaped fashion.

The amplitude of the response of output to monetary policy is realistic. After a one-percentage-point decrease of the nominal interest rate, the literature estimates that output increases by around 0.8%. In our simulation, output rises by 0.7% in the same situation.

Third result: monetary nonneutrality in the long run

Monetary policy is also nonneutral in the long run. This means that steady-state inflation rate affect the steady-state employment rate. Such nonneutrality is illustrated below. The figure gives the relationship between steady-state inflation, measured as an annual rate, and employment, measured as a percentage deviation from employment in the zero-inflation steady state:

The property that higher steady-state inflation leads to higher steady-state employment is consistent with evidence that higher average inflation leads to lower average unemployment. In the United States, a permanent increase in inflation by 1 percentage point reduces the unemployment rate between 0.2 and 1.3 percentage points, depending on the period.

Fourth result: intense dislike for inflation

In the model, when consumers observe inflation, they misperceive price markups as higher and transactions as less fair, which lowers their utility and triggers a feeling of displeasure. Thus, in our model as in Shiller’s survey, consumers perceive higher markups during inflationary periods and are angered by them.

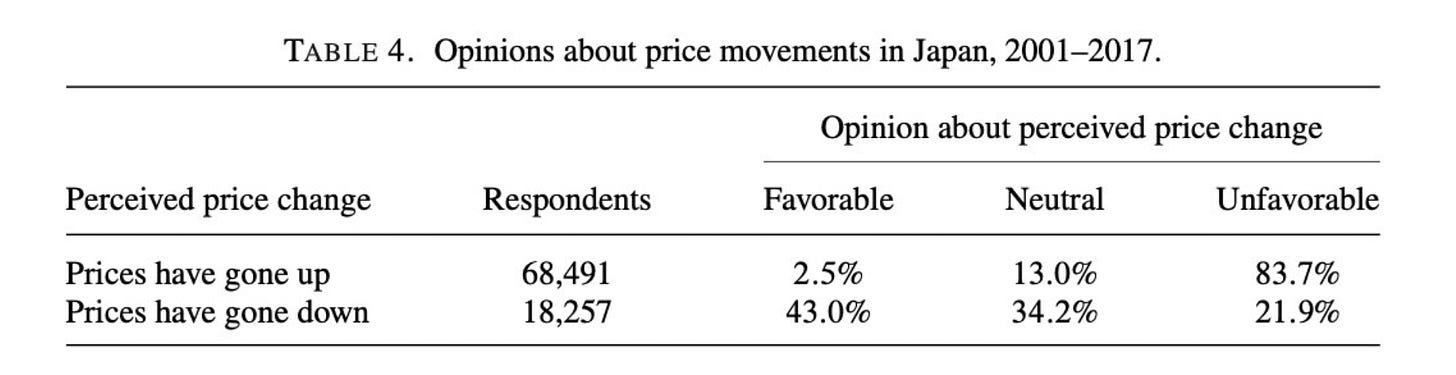

Conversely, upon observing deflation, consumers in the model would believe that price markups are lower and transactions more fair, which would boost their utility and trigger a feeling of happiness. Hence, our model predicts not only that consumers dislike inflation, but also that they enjoy deflation.

A large-scale survey run by the Bank of Japan between 2001 and 2017 paints exactly this patterns. During the period, Japan alternated between inflation and deflation. Respondents were dismayed by price increases and inflation, but they saw price decreases and deflation favorably:

Conclusion

Adding assumptions consistent with real-world evidence into macro models might make them more relevant and accurate. It might help understand people’s actions and reactions. Eventually it might even improve policy.

In the meantime, any interested reader can find the complete code to simulate the model on GitHub. In particular, the code produces the graphs in this post.

Of course, to understand fully inflation dynamics during the pandemic, and people's reaction to it, the model should be extended with supply-chain bottlenecks and so on.

We need both assumptions. With fairness concerns but a full understanding of costs, or with no fairness concerns but mistaken beliefs, none of the results would occur.