The Fake Problem of Fake Vacancies

Vacancy data and their use by the Federal Reserve have been questioned recently—for no good reasons.

Since May 2022, the Federal Reserve has been tightening monetary policy. It has given two justifications for its actions. The first is obvious: inflation is too high. The second is more unusual: the number of vacancies per unemployed people—a ratio called labor market tightness in macro— is too high.

Following the Fed’s emphasis on vacancies and labor market tightness, a number of media articles and blog posts have been written to criticize vacancy data and their use by the Federal Reserve. In this post, I review these criticisms and argue that they have no solid empirical or theoretical basis. There is a lot to learn from vacancy data, and it is a good thing that the Fed is using them to inform its policy.

The Fed’s Use of Vacancy Data

When Jerome Powell announced in press conference in May 2022 that the Federal Reserve was going to start tightening monetary policy, a good part of the discussion with the journalists revolved around vacancies and the number of vacancies per unemployed people (aka labor market tightness).

First, Powell noted that the labor market in May 2022 was extremely tight:

Vacancies are at such an extraordinarily high level. There’re 1.9 vacancies for every unemployed person, 11.5 million vacancies, 6 million unemployed people. So we haven’t been in that place on the vacancy, sort of the vacancy/unemployed curve, the Beveridge curve. We haven’t been at that sort of level of a ratio in the modern era.

Powell had a point: in the US, you have to go back to the end of World War 2 to find a labor market tightness above 1.9. In response to Powell’s statement, journalist Howard Schneider asked which tightness the Fed might target:

You’ve cited the 1.9 to 1 figure so often now, I’ve got to ask you, what would be a good figure there?

Powell then responded:

I think when we got to one-to-one in the, you know, in the late teens, we thought that was a pretty good number.

Powell has the correct intuition here. In a model calibrated to the US labor market, a labor market tightness of 1 is indeed what the Fed should target: it is the efficient labor market tightness, corresponding to full employment.

Since the May 2022 press conference, Powell has continued to talk about labor market tightness. This was again the case a few days ago, when he announced that the Fed would raise rates further to 5%:

Right now, you have a labor market that's still extraordinarily tight. You still got 1.6 job openings, even with the lower job openings number for every unemployed person.

The narrative of fake vacancies

The gist of the criticisms leveled at vacancy data and the Federal Reserve is that many vacancies are “fake vacancies”. They do not actually represent one single position, and may not lead to a new hire. Therefore the Fed should not use vacancy data to guide policy.

A recent article by CBS News, titled “Fake job listings are a growing problem in the labor market”, is a good example of the narrative of fake vacancies.1 The CBS News article focuses on the recent period, but other observers of the labor market even argue that vacancy numbers are vacuous in general and should never used by the Fed. A good representative of this view is an August 2022 blog post from Employ America, titled “A Vacant Metric: Why Job Openings Are So Unreliable“.2

Let’s go over the various criticisms raised by these two pieces.

1: Vacancies are not well measured in official statistics

A first claim by both pieces is that vacancies are not well measured in official statistics: “the empirical sources for vacancy data are shaky at best”, “the threshold for reporting a vacancy in official statistics is low, making it difficult to infer search intensity from the raw number of vacancies, potentially inflating the number of observed vacancies”.

However, vacancies are measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), just like all other labor market statistics. Specifically, the number of vacancies is measured monthly by the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). The survey asks firms to report the number of vacancies that they currently have, where a vacancy is defined as follows:

A specific position exists and work is available.

The job could start within 30 days.

The firm is actively recruiting workers from the outside to fill the position.

These questions are similar to the questions asked by the BLS to workers in the Current Population Survey (CPS) in order to assess whether they are unemployed or not. Workers have to say whether they are willing to work, available to start work immediately, and actively searching for a job. So vacancy data are of the same quality as unemployment data, and if we use one, there is not reason not to use the other.

The threshold for reporting a vacancy is that same as the threshold for reporting being unemployed. The firm and the worker have to answer that they have been actively searching on the labor market—for instance through online job portals.

More generally, most labor market statistics come out of the JOLTS and CPS. All these statistics are obtained by surveying firms and workers. So there is no reason to believe that vacancy numbers are more poorly measured than the rest.

2: It is very easy to post vacancies on online job boards

A second point brought up by both pieces are online job boards: “plentiful free job-listing tools have made it much easier to list a job, while the boom in remote work during the pandemic has pushed the figures even higher”, “for another example of the fragility of this kind of measurement, consider the Help Wanted Online (HWOL) series from the Conference Board”.

As noted above, the vacancy numbers used by the Fed do not come from online job boards: they are measured through JOLTS. So what happens on online job boards is irrelevant.

As a side note, earlier research finds that the internet and online job portals do not have much effect on the job market. So there is no reason to believe that the job market is going to become fundamentally different because of online job portals.

Indeed, looking at the academic job market, it does not seem that the amount of effort required to recruit colleagues is appreciably diminished by online job portals. Most of the recruiting time is spent on four things: reading applications and papers; interviewing candidates; flying out candidates; building a case and debating with department colleagues. None of these four main tasks are affected by the presence of online job boards.

3: Firms post more than one vacancy per hire

A third issue, mentioned by the CBS News piece, is that firms post more than one vacancy per hire—which leads them to believe that some vacancies are fake since they do not result in a hire: “there are companies that have 10 job listings and are only hiring two people at the moment”, “many hiring managers told CBS MoneyWatch that they have started listing jobs in multiple locations to expand their pool of candidates”, “when you have fewer candidates per opening, you have to be more creative, create more job titles for positions”.

But this is exactly how firms behave in matching models! In the model, if a firm wants to recruit one worker this month but knows that a vacancy is only filled with probability 1/3, then the firm will post 3 vacancies to hire one worker in expectation.

And of course firms will post vacancies in different locations, for different positions, and with different modalities (online or in-person) to increase the chances of matching with a suitable worker. Posting the exact same vacancy many times would not be effective.

The key point is that in matching models, vacancies do no represent actual position but recruiting effort—an effort to try to find workers through the matching process. And this is also what vacancies represent in reality, as ZipRecruiter chief economist Julia Pollak explains in the CBS article:

When you have fewer candidates per opening, you have to be more creative… The high openings figure does partly reflect recruiting intensity, and not actual roles and seats and slots.

The bottom line is firms behave in reality exactly as in the model. The fact that firms post several vacancies per position does not mean that we should discount vacancy data. This behavior is what matching models predict.

4: Vacancies are just noise

Another complaint raised by the two pieces is that vacancy numbers are just too noisy to be helpful: “vacancies are a flawed indicator of the state of the labor market“, “vacancies are a poor proxy for labor market strength”, “job openings are so unreliable”, “economists have long expressed skepticism of the number of monthly job openings reported by the government”.

If vacancies were a vacant metric, we would expect them to be just noise. But vacancies and unemployment are strongly negatively correlated. They describe a well-defined Beveridge curve. In fact the Beveridge curve is one of the most robust macro relationships—how would it arise if vacancy data were vacuous?

Below is the US Beveridge curve in the past 25 years (coming from figure 5 in this paper), based on the JOLTS numbers:

Given that unemployment and vacancies come from two entirely different sources (JOLTS and CPS), it is striking that they comove so closely.

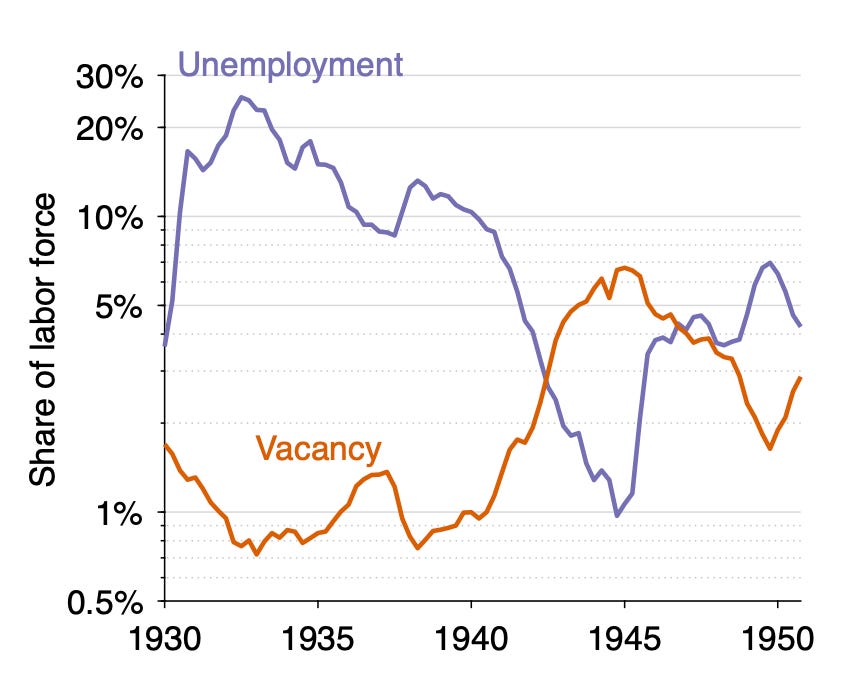

This close relationship between unemployment and vacancies exist in the US even in the pre-JOLTS period. Papers by Regis Barnichon and Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau and Zhang Lu compute vacancy numbers for the pre-JOLTS period using data from the Conference Board and other sources. They harmonize these data to create vacancy numbers going back to 1930. And the negative relationship between unemployment and vacancies continue to appear clearly, even when data come from disparate historical sources cobbled together.

Notice how unemployment and vacancy rates are the mirror image of each other in the 1951–2019 period (from figure 1 in this paper):

The same is true during the earlier, 1930–1950 period (from figure 9 in the same paper):

5: Vacancies are meaningful only in a single toy models

The final criticism, raised by the Employ America post, is that vacancies are only meaningful in the textbook Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides model, which is too simple to describe the reality of the labor market: “vacancies are prominent due to highly-stylized models where vacancy posting drives labor market dynamics”, “The models that give significant importance to the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio as a labor market indicator rely on highly abstracted models of job search and unemployment. These models greatly simplify many salient features of real-world job search and unemployment activity.”

This is actually inaccurate. Labor market tightness (the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio) determines the state of the labor market in a broad range of labor market models. In any model with a Beveridge curve and some cost of recruiting, there is an efficient labor market tightness that the Fed should target to maximize social welfare. Furthermore, the efficient labor market tightness can be computed from a few sufficient statistics.

So, in many, many realistic models of the labor market, labor market tightness (which requires vacancies to be computed) is the appropriate variable for policymakers to monitor. This is true not only for monetary policymakers but also for fiscal policymakers.

Why are fake vacancies an issue now?

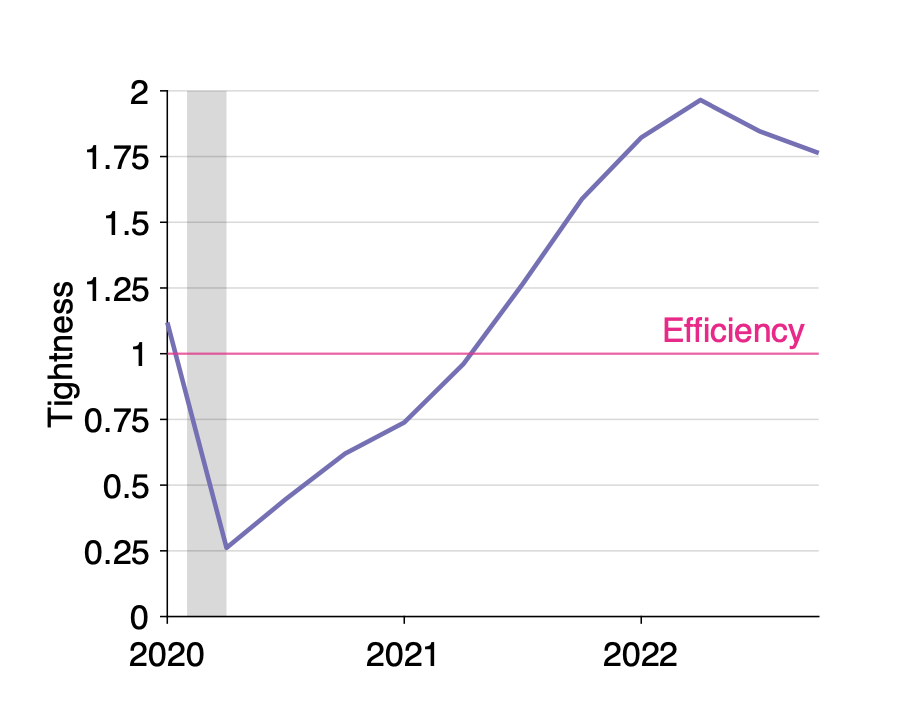

Firms have been posting vacancies for a century at least, so why do vacancies only appear fake now? The reason is that the labor market is currently exceptionally tight. It is the tightest it has been since the end of World War 2. Labor market tightness has been above 1.5 since the fall of 2021. The last time it had reached 1.5 was in 1945!

Such exceptional tightness means that vacancies are filled at the slowest rate in the postwar period. Indeed, in a tight market, jobseekers find jobs at a high rate, but firms fill vacancies at a slow rate—as predicted by matching models.

Because vacancies are filled at such slow rate, the number of vacancies posted for one actual position has exploded—creating an impression of fake vacancies. But this was expected: this is exactly what matching models predict. Firms post several vacancy per position because they realize that the yield of each vacancy is low.

Conclusion

Although vacancies are not discussed much in typical macro work, there is an old and large literature that studies vacancies and explains how to measure them. In fact that literature is as old as the literature studying unemployment, going back to the work of William Beveridge in 1944, Albert Rees in 1957, and Katharine Abraham in 1983 and in 1987.

Vacancy numbers are now well measured every month by the JOLTS. There is much to be learnt from these data. Looking at vacancies—together with other labor market statistics such as unemployment—is required to have a complete understanding of the state of the labor.

For instance, comparing the numbers of vacancies and unemployed workers indicates whether the labor market is inefficiently slack, efficient (that is, at full employment), or inefficiently tight. Looking at unemployment alone is not sufficient to establish such a diagnosis.

In addition, the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio is an accurate leading indicator of recessions. In the US since 1930, recessions tend to start a few quarters after the ratio has peaked, and to stop when the ratio starts recovering (recessions are denoted by the shaded areas; from figure 12 in this paper):

The post-pandemic vacancy-to-unemployment ratio peaked at 2 in the second quarter of 2022 and has been falling since (from figure 6 in the same paper):

The cooling of the labor market would not be visible by looking at the unemployment rate alone, which is still at record low levels.

Thank you to Sam Levey for referring me to this blog post.

Hi Pascal,

How do you reconcile the trend in vacancies over the 20 years? If you try to predict vacancies using quits or unemployment, you get a significant time trend. And rising mismatch between 2001-2019 seems to be very unlikely during a period of falling unemployment and falling wage growth.