March Labor-Market Update

Labor-market numbers for March 2024 are in. The US labor market remains inefficiently tight—in fact it is slightly tighter than in February.

US labor-market numbers for March 2024 just came out. This post uses the latest numbers on vacant jobs and unemployed workers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to compute three key statistics:

Labor-market tightness

Efficient unemployment rate

Unemployment gap

The US labor market tightened very slightly since February, so it remains inefficiently tight.

New developments

The US labor-market statistics for March 2024 are as follows:

Unemployment rate: u = 3.8%. This is down from 3.9% in February.

Vacancy rate: v = 5.2%. This is the same as in February.

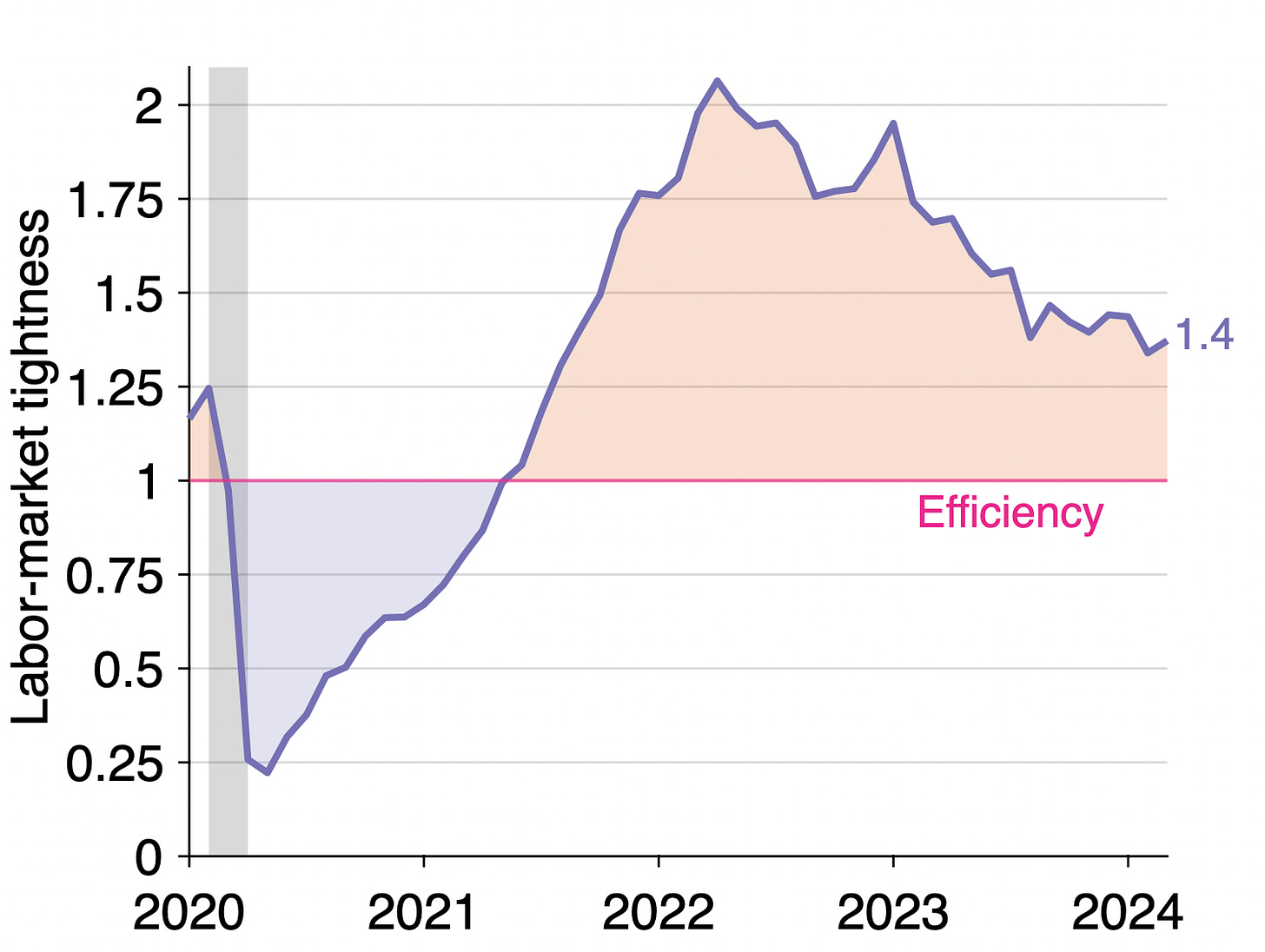

Labor-market tightness: v/u = 5.2/3.8 = 1.4. This is up from 1.3 in February.

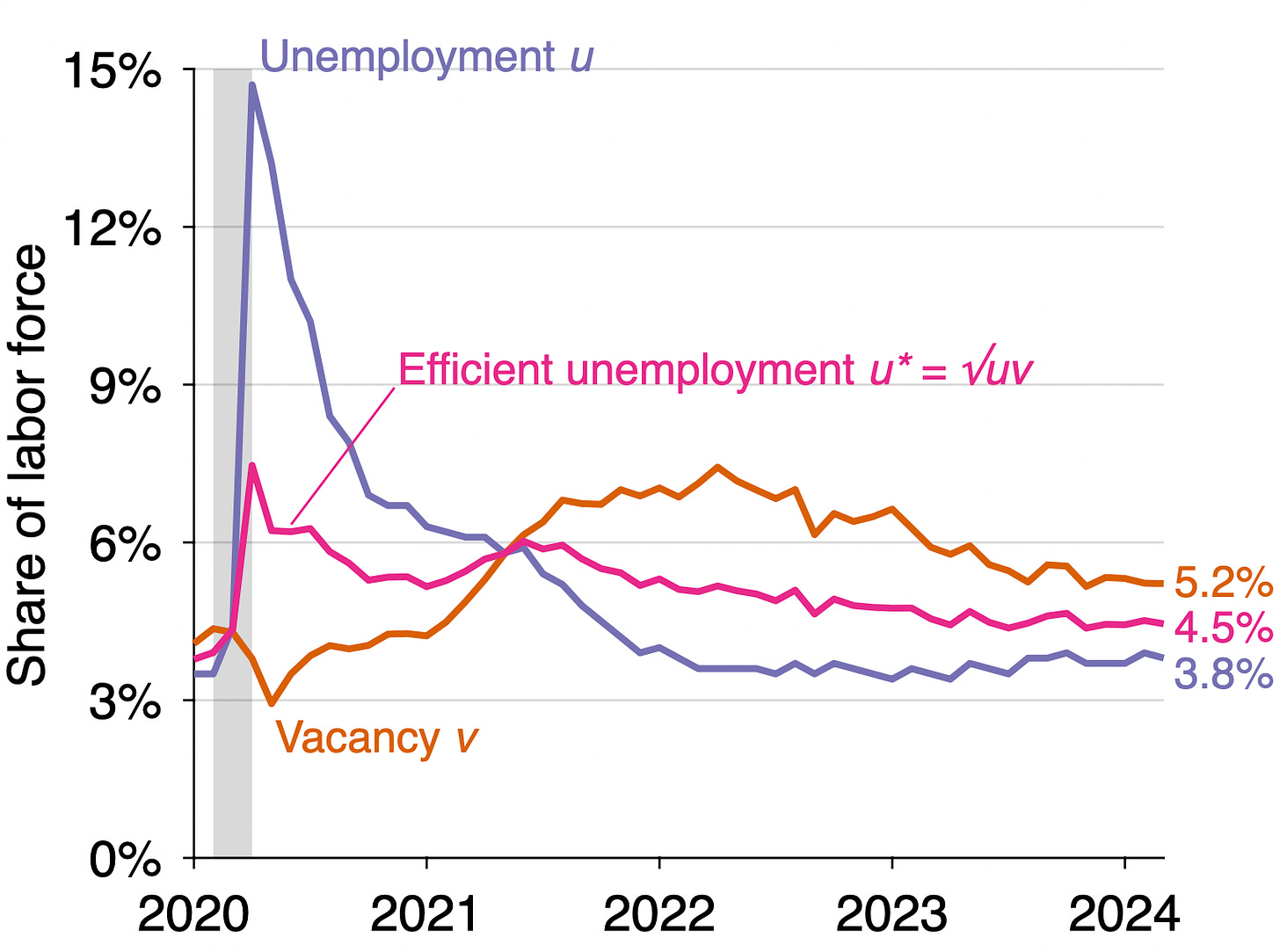

Efficient unemployment rate: u* = √uv = √(0.038 × 0.052) = 4.5%. This is the same as in February.

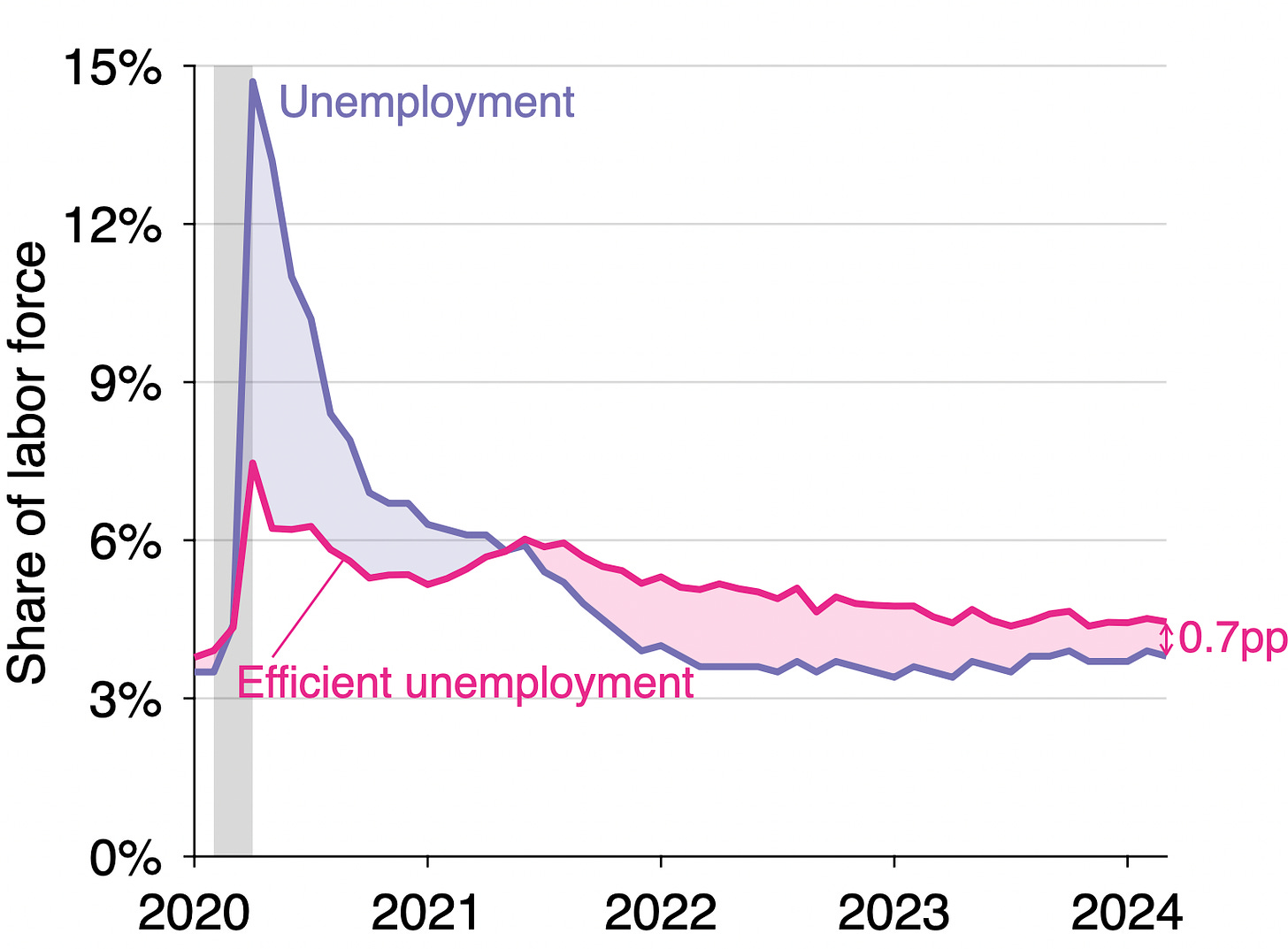

Unemployment gap: u – u* = 0.038 – 0.045 = –0.7pp. The gap widened from –0.06pp in February.

Background for readers just joining us

The construction of the unemployment rate and vacancy rate from data provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics is detailed in a previous post. The formula u* = √uv for the efficient unemployment rate is derived in a recent paper by Emmanuel Saez and me. The formula implies that the labor market is efficient when there are as many unemployed workers as vacant jobs (u = v); inefficiently tight when there are fewer unemployed workers than vacant jobs (u < v); and inefficiently slack when there are more unemployed workers than vacant jobs (u > v).

Is the US labor market is too tight or too slack?

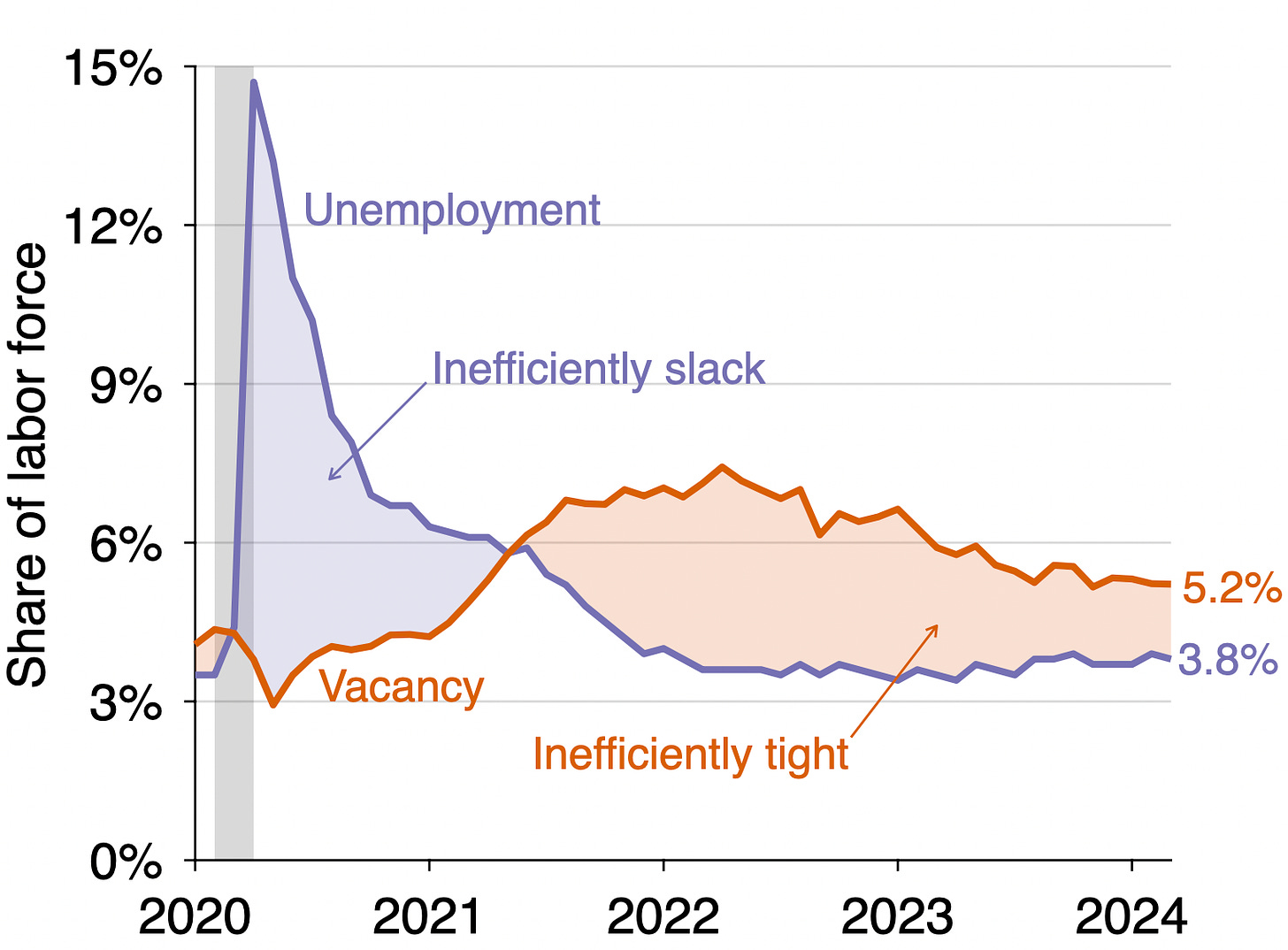

Since the vacancy rate is above the unemployment rate (5.2% > 3.8%), the US labor market remains inefficiently tight. This means that the labor market is above full employment: the labor market is so hot that an excessive amount of labor is devoted to recruiting and hiring instead of producing. The labor market has been inefficiently tight since May 2021:

We can also see that the US labor market is inefficiently tight by looking at labor-market tightness v/u. Tightness remains above unity (1.4 > 1), which signals that the labor market is inefficiently hot:

How far is unemployment from its efficient rate?

Since the labor market is inefficiently tight, the actual unemployment rate remains below the efficient unemployment rate. The graph below illustrates the construction of the efficient unemployment rate:

The efficient unemployment rate is 0.7 percentage point above the actual unemployment rate (u* = 4.5% while u = 3.8%). This negative unemployment gap is another manifestation of an inefficiently tight labor market. Below is the evolution of the unemployment gap over the course of the pandemic. The unemployment gap has been negative (u* > u) since the middle of 2021:

Implications for immigration policy

Last month’s post discussed the implications for monetary policy of the current negative unemployment gap. Such negative unemployment gap—or excessive labor market tightness—has implications for other policies too. In particular, it matters for immigration policy.

In a recent paper, I argue that the overall effect of immigration on native welfare (welfare of native workers and native firm owners) depends on the state of the labor market. Immigration has a negative effect on the welfare of native workers because, in the short run, it increases the unemployment rate of native workers. But immigration has a positive effect on the welfare of native firm owners because it makes it easier for firms to recruit.

When the labor market is inefficiently slack, immigration reduces native welfare because then the reduction in native labor income swamps the increase in native firm profits. But some immigration improves welfare when the labor market is inefficiently tight, because then native firm profits increase more than native labor income drops.

An implication is that optimal immigration policy is procyclical: there should be more immigration in good times than in bad times. Given that the labor market is currently inefficiently tight, immigration improves native welfare—because immigrants fill jobs that would otherwise be vacant. According to the model, now is therefore a good time to let immigrants join the US labor market.

This analysis shows no role played by wage levels. After all, if there is a shortage of candidates (supply) relative to vacancies (demand), one would expect the price of labor (real wage) to rise. Unskilled wages are where they were before the pandemic while profits have risen:

https://mikebert.neocities.org/HS-dropout-wage.gif

Looking at the chart in the article it seems that recently the gap between vacancies and unemployment rate has been closing by falling vacancies. It would seem that businesses are deciding to go without new hires. Could it be that the vacancies reported are those that companies would *like* to fill for pre-pandemic real wage levels, but can't fill in today's world without going back to pre-pandemic profit levels?

Who should do what on the basis of your finding that the labor market is inefficiently tight? The Fed should not reduce the EFFR?