December Labor-Market Update

The US labor market tightened in December and remains tighter than full employment.

Main message: The US labor market tightened between November and December. The US labor market is tighter than full employment, with a labor-market tightness of 1.18. The current FERU is 4.4%, and the current unemployment gap is -0.3pp. The current recession probability is 26%.

The US labor-market data for December 2024 have just come out. This post uses the latest numbers on vacant jobs and unemployed workers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to compute labor-market tightness, full-employment rate of unemployment (FERU), unemployment gap, and recession probability.

New developments

The US labor-market statistics for December 2024 are as follows:

Unemployment rate: u = 4.1%. This is down from 4.2% in November.

Vacancy rate: v = 4.8%. This is up from 4.7% in November.

Labor-market tightness: v/u = 4.8/4.1 = 1.18. This is up from 1.10 in November.

FERU: u* = √uv = √(0.041 × 0.048) = 4.4%. This is the same as in November.

Unemployment gap: u – u* = 0.041 - 0.044 = –0.3pp. The gap widened from -0.2pp in November.

Recession indicator = 0.43pp. This is down from 0.44pp in November.

Recession probability = (0.43-0.3)/(0.8-0.3) = 26%. This is down from 28% in November.

Background for readers just joining us

The FERU formula u* = √uv is derived in a paper with Emmanuel Saez that will come out in the Fall 2024 issue of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. The formula implies that the labor market is at full employment when there are as many unemployed workers as vacant jobs (u = v); inefficiently tight when there are fewer unemployed workers than vacant jobs (u < v); and inefficiently slack when there are more unemployed workers than vacant jobs (u > v). Data and code for the paper are available on GitHub.

The recession indicator and recession probability are developed in another paper with Emmanuel. The recession indicator combines data on job vacancies and unemployment. The indicator is the minimum of the Sahm indicator—the difference between the 3-month trailing average of the unemployment rate and its minimum over the past 12 months—and a similar indicator constructed with the vacancy rate—the difference between the 3-month trailing average of the vacancy rate and its maximum over the past 12 months. When the indicator reaches 0.3pp, a recession may have started; when the indicator reaches 0.8pp, a recession has started for sure. The data and code used in the paper are also available on GitHub.

Is the US labor market inefficiently tight or slack now?

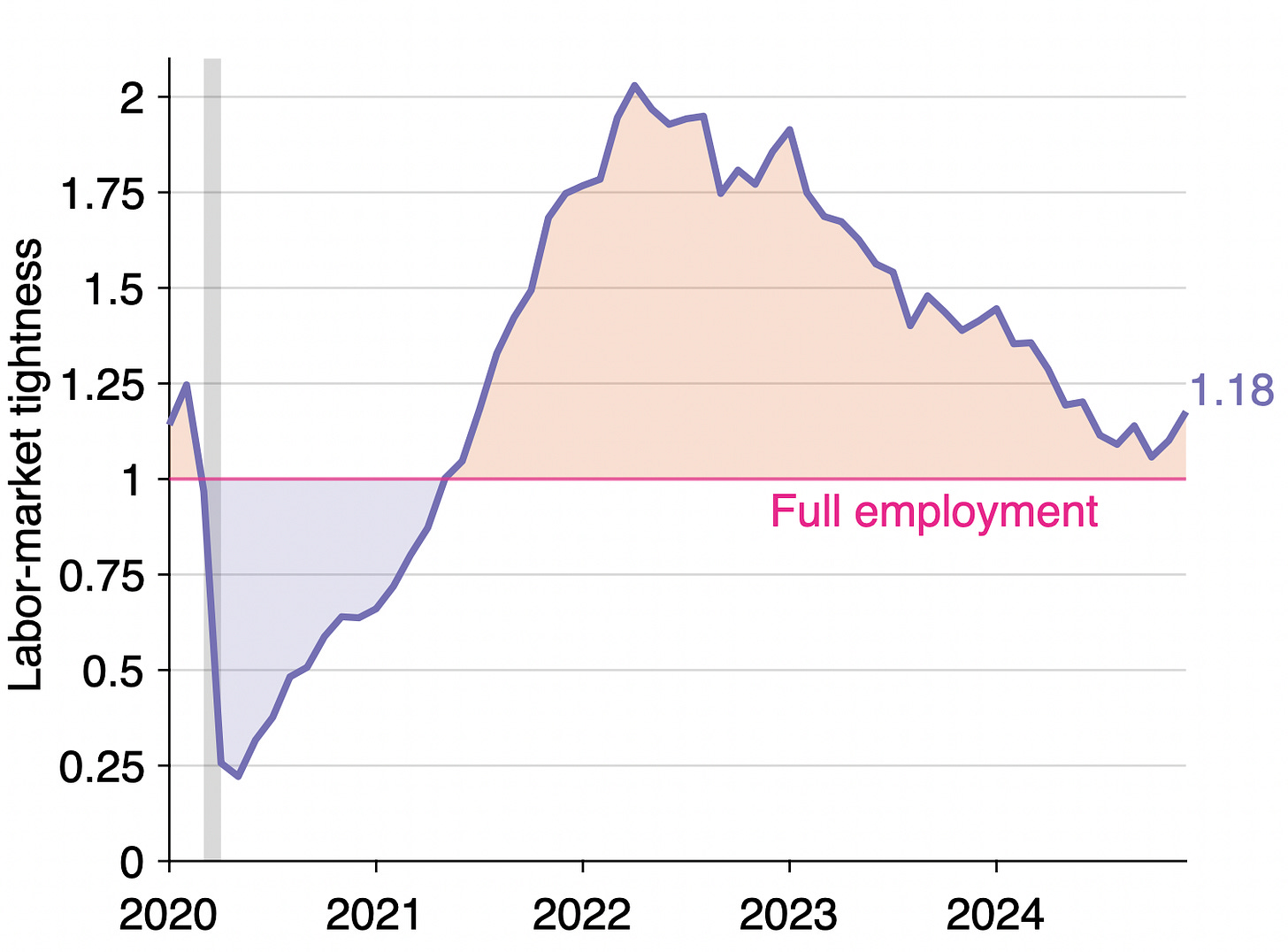

Coming back to the December 2024 situation, we see that the vacancy rate is above the unemployment rate (4.8% > 4.1%), so the US labor market remains inefficiently tight. The labor market has been inefficiently tight since May 2021:

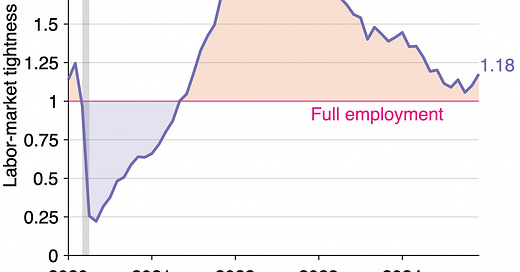

We can also see that the US labor market is inefficiently tight by looking at labor-market tightness v/u. Tightness remains above unity (1.18 > 1), which signals that the labor market is inefficiently hot:

How far is unemployment from the FERU?

Since the labor market is inefficiently tight, the actual unemployment rate remains below the FERU. The graph below illustrates the construction of the FERU, which is the geometric average of the unemployment and vacancy rates:

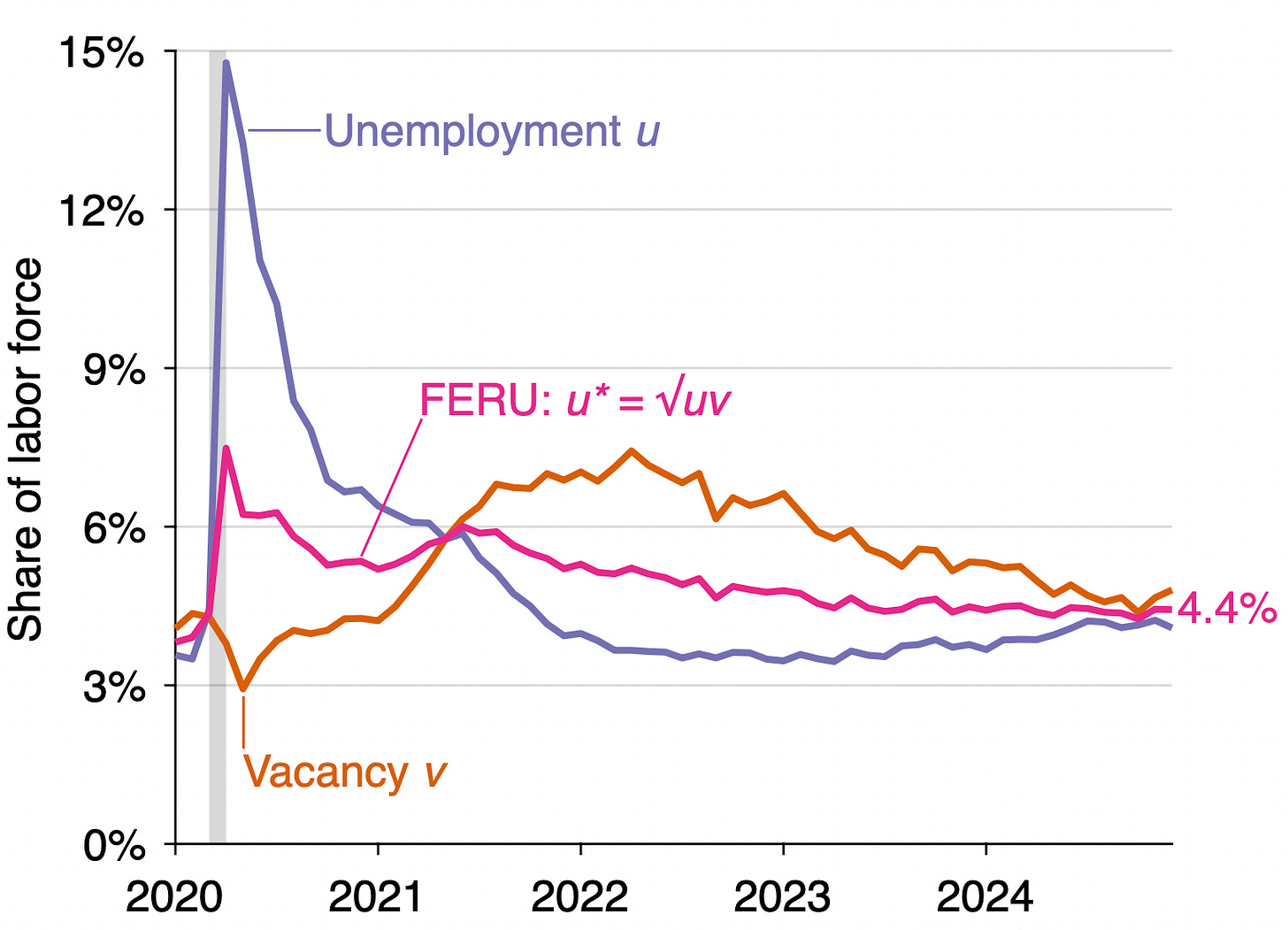

The FERU is 0.3 percentage point above the actual unemployment rate. This negative unemployment gap is another manifestation of an inefficiently tight labor market. Below is the evolution of the unemployment gap over the course of the pandemic. The unemployment gap has been negative (u* > u) since the middle of 2021:

Given how much the labor market has cooled, have we entered a recession?

To determine whether the economy has entered a recession, we build a new indicator. This indicator is the minimum of the Sahm indicator, which is built from the unemployment rate, and a similar indicator built from the vacancy rate.

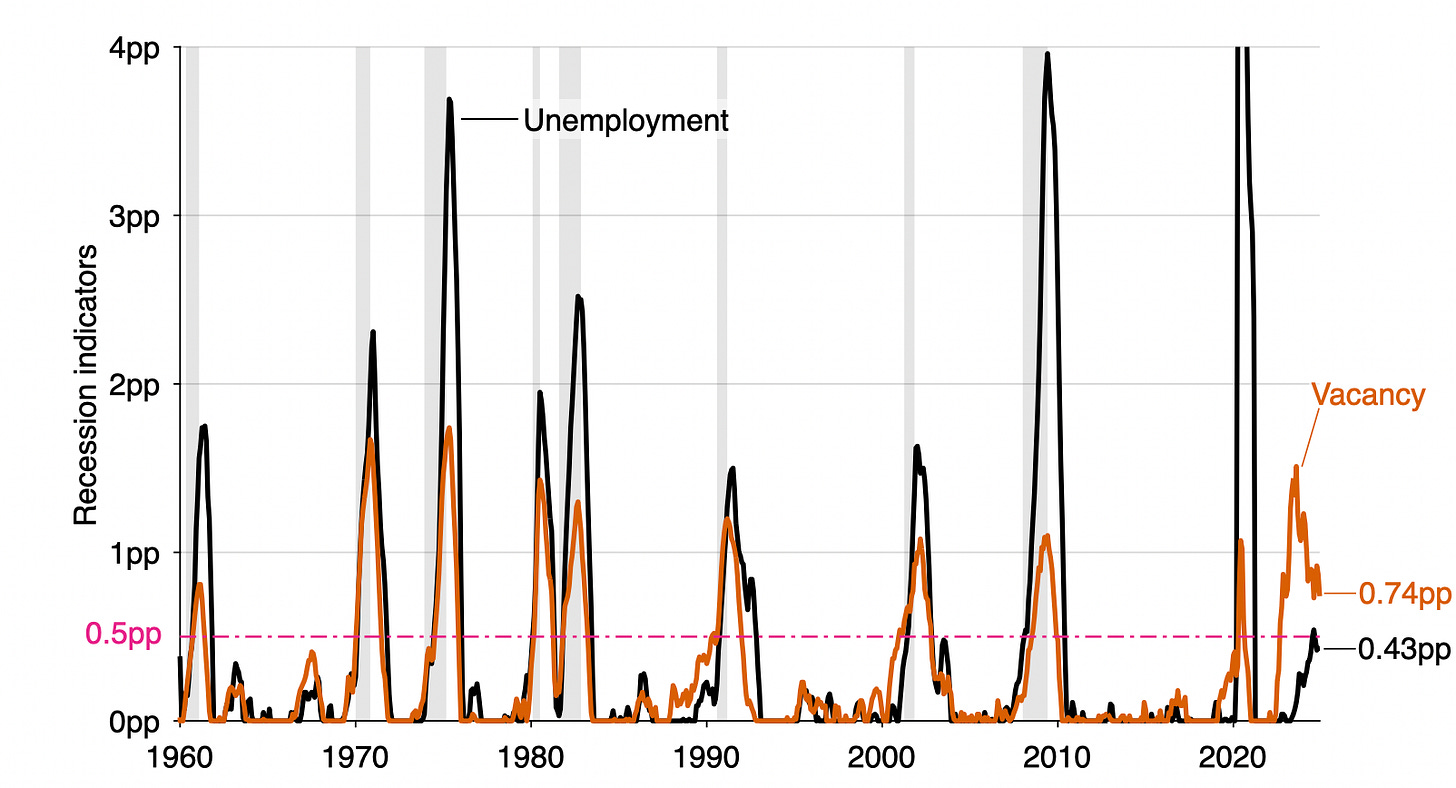

Below is the standard Sahm indicator (black line) and the threshold of 0.5pp that is used in the Sahm rule. The Sahm indicator is the difference between the 3-month trailing average of the unemployment rate (plotted above) and its minimum over the past 12 months. The Sahm rule says that a recession might have started whenever the unemployment indicator crosses the threshold of 0.5pp. The Sahm rule was triggered in August (the indicator reached 0.54pp > 0.5pp), but it was untriggered in the past 3 months (the indicator is now 0.43pp < 0.5pp). So the message from the Sahm rule is muddled:

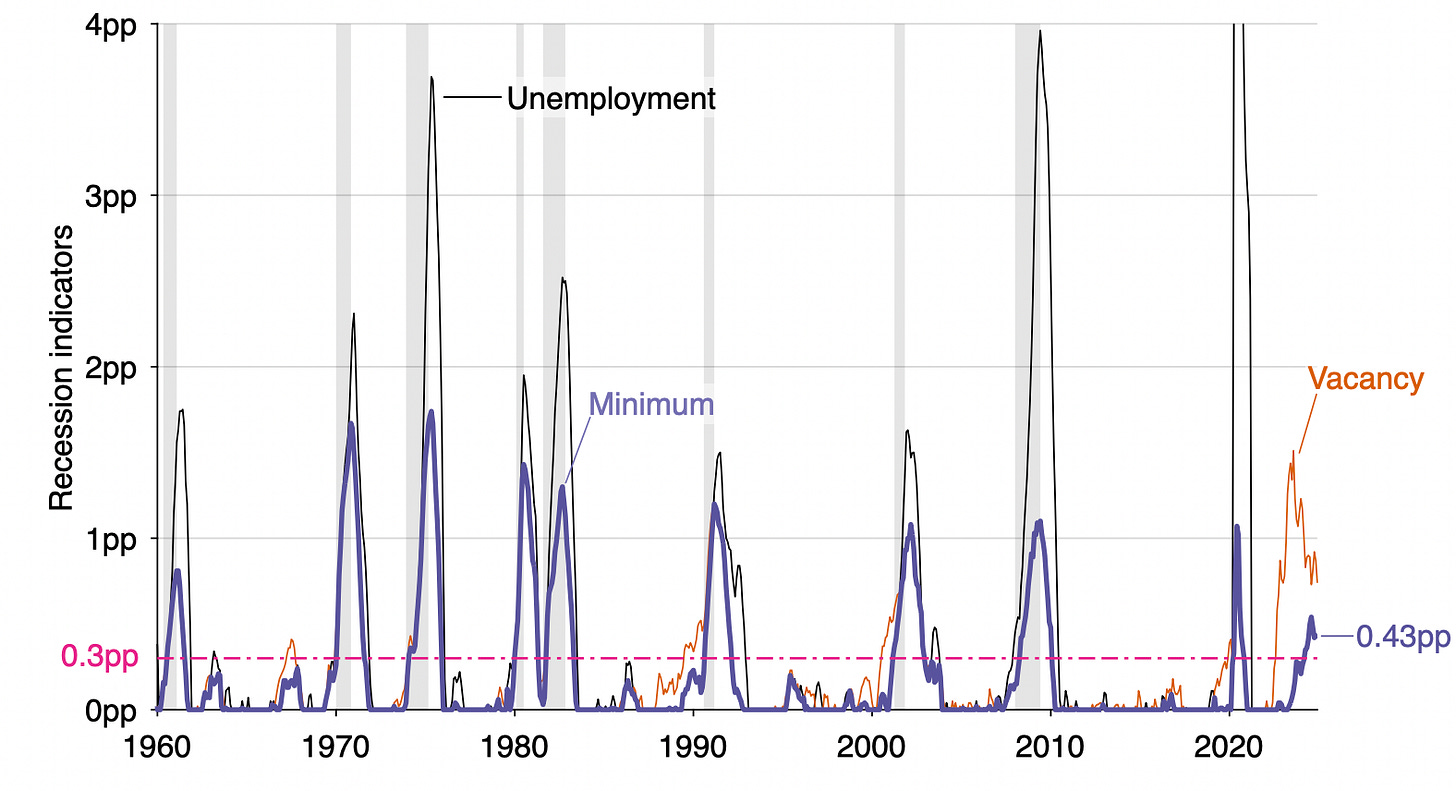

We can construct the same type of indicator with the vacancy rate (orange line above). Indeed, job vacancies start falling quickly at the onset of recessions, when unemployment starts rising. Requiring that both unemployment and vacancies rise gives a more accurate and—maybe counterintuitively—more rapid recession signal. Here is the indicator that we build as the minimum of the unemployment and vacancy indicators:

Because this minimum indicator is less noisy than either the unemployment or the vacancy indicator, we can lower the recession threshold from 0.5pp to 0.3pp and detect recessions faster. On average between 1960 and 2022, our new recession rule, based on the minimum indicator, detects US recessions 0.8 month after they have started, while the Sahm rule detects them 2.1 months after their start.

Our minimum indicator reached 0.3pp between March and April 2024, so the recession might have started then. The current value of the minimum indicator is 0.43pp, so well above the recession threshold of 0.3pp.

What is the probability that we are now in recession?

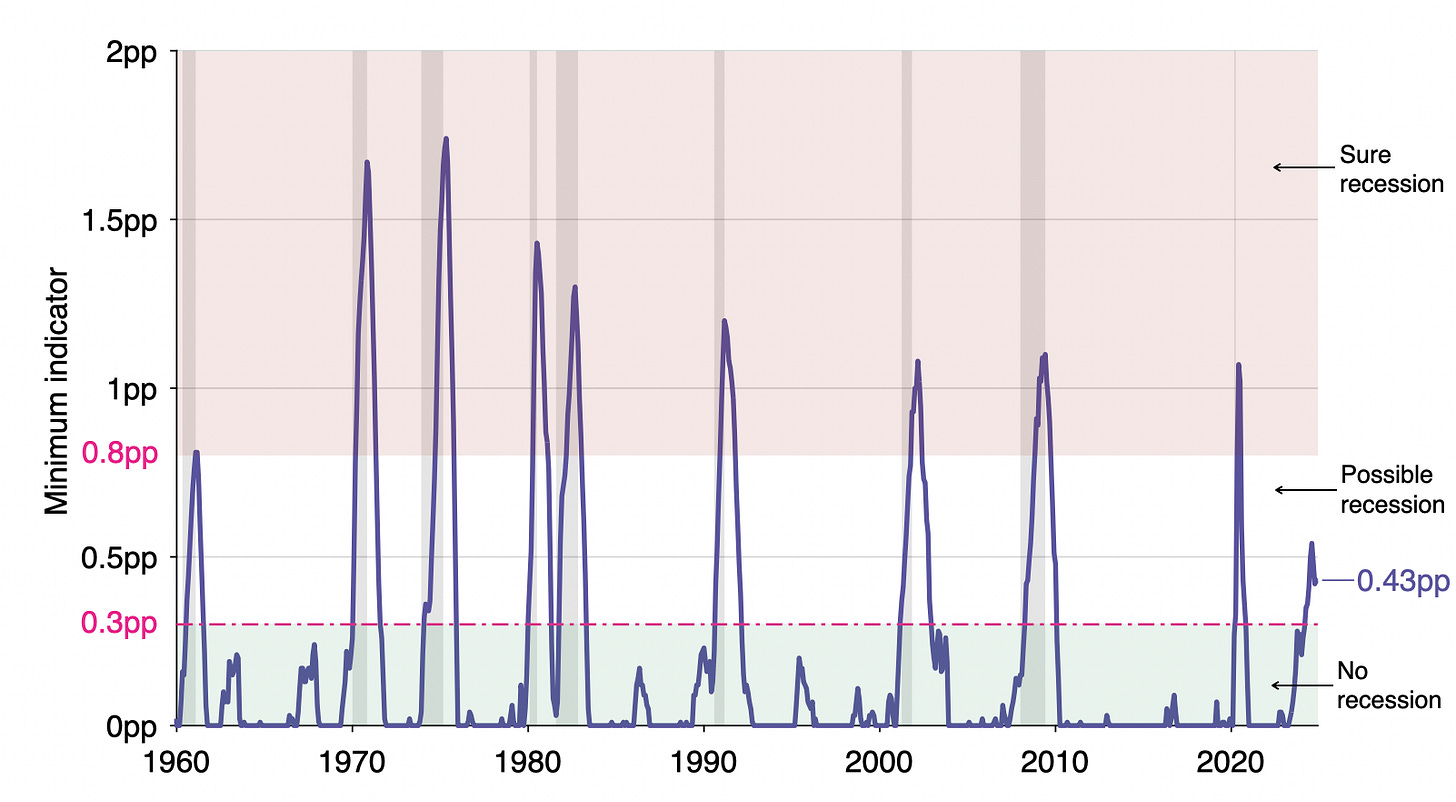

A one-sided recession rule such as the Sahm rule tells us whether a recession might have started. To know what is the likelihood that a recession has started, we propose a two-sided recession rule.

The bottom threshold is the lowest value that generates no false positives over 1960–2022. A false positive is when the rule predicts a recession that does not materialize. This bottom threshold is 0.3pp.

The top threshold is the highest value that generates no false negatives over 1960–2022. A false negative is when the rule does not catch an actual recession. This top threshold is 0.8pp.

The rule says the following. When the minimum indicator is below 0.3pp, we cannot say that a recession has started. When the minimum indicator is between 0.3pp and 0.8pp, the recession might have started. And when the minimum indicator is above 0.8pp, the recession has started for sure. The two-sided rule operates as follows:

With December 2024 data, the minimum indicator is at 0.43pp, so the probability that the US economy is now in recession is (0.43-0.3)/(0.8-0.3) = 26%. This probability captures the fact that we do not know exactly what is the true threshold between a recession and a non-recession. From historical data, we learn that the true threshold is somewhere between 0.3pp and 0.8pp. This is because any threshold between 0.3pp and 0.8pp produces no false positives and no false negatives, so it perfectly separates recessions from non-recessions. The recession probability captures the share of the threshold range that has been covered.

What are the implications of full employment for inflation?

In a newly revised paper, Emmanuel and I study the connection between the unemployment gap and inflation. In the United States, in the past decades, it does seem that the divine coincidence holds: inflation is at its target level of 2% whenever the labor market is at full employment—whenever the unemployment rate is at the FERU. Based on this evidence, and the fact that the labor market is still somewhat above full employment, we would expect inflation to remain somewhat above 2%.

It might seem surprising that the divine coincidence holds in reality, but in the paper we show that the divine coincidence arises naturally in a Beveridgean (not New Keynesian) model of the Phillips curve. In that model, price dynamics are driven by slack instead of marginal costs: sellers raise prices when a lot of customers demand their goods and services, and they cut prices when demand falls. In such a world—which does not seem so unrealistic—the divine coincidence holds. Monetary policy is greatly simplified in that case because the Fed’s two mandates—stable prices and full employment—coincide. In the current situation, both mandates indicate that the Fed should not cut rates further, since inflation remains above 2% and the labor market remains above full employment.

Paschal,

I am a novice things economics and economic research, but reading your Labor-Market updates has been eye-opening. I look forward to your January 2025 update and all incoming updates.

Could the FERU be calculated for each state? Or is the data only on the national level?